Donkey

anorak

anorak is Lukas Ludwig & Johanna Markert; with James Rushford (voice, music); and Lina Ludwig (copy editing)

Media

Image

Text (English and German)

Audio (English; 1 hour)

Downloads

Themes

Collections

Donkey is a fragment of a curatorial research project—an engagement with the donkey as cultural product, with melancholy and affirmation, of the carrying of heavy loads and the relieving of burdens, of language and the desire to refuse, of power and devotion, of mysticism and mystical transfiguration. Donkey is an object of projection, a mirror of desires. Donkey is a vessel that is slowly filled and rapidly emptied.

Donkey ist ein Fragment einer kuratorischen Recherche – eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem Esel als Kulturprodukt, mit Melancholie und Affirmation, mit dem Tragen schwerer Lasten und dem Abwerfen der Last, mit Sprache und der Lust an Verweigerung, mit Potenz und Devotion, mit Mystik und mystischer Verklärung. Donkey ist eine Projektionsfläche, ein Spiegel von Sehnsüchten. Donkey ist ein Gefäß, das langsam gefüllt und schnell ausgegossen wird.

Written during a COVID-lockdown in Spring 2021, Donkey is a means to engage with the author’s own depression, a denial of loneliness, an effort to reinscribe oneself in the world.

Loading Audio

Sound: Donkey read by James Rushford, 2022.

EN: Larry Johnson, Untitled (Ass), 2007. Color photograph framed, 57.63 x 62.63 x 1.5 inches / 146,4 x 159,1 x 3,8 cm. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

DE: Larry Johnson, Untitled (Ass), 2007. Farbfotografie, gerahmt: 146,4 x 159,1 x 3,8 cm. Mit freundlicher Genehmigung der David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Against a white background, a pencil-drawn cartoon donkey looks back at the hand drawing it. The eraser at the end of a pencil rubs into the donkey's anus. The donkey smiles, almost excited by the touch of the artist.

Sound: The gates of Béla sEI from APPENDIX (2020) by Lukas Ludwig.

Part I: Onos Lyras, or: The Donkey with the Lyre

I have long been fascinated with donkeys. And even though the animal has been accompanying me for quite a while—or else I have been carrying it around with me for quite a while—I find it difficult to clearly define my donkey, to give it shape, to position it. This calls to mind the donkey’s often-invoked stubbornness, and a certain stuffed donkey comes onto the scene—but more on that later. One thing’s for certain: enough has already been expressed here to suggest that the donkey will prove to be a very complex and resistant companion on our journey. What’s more, it will even come to resemble a kind of trickster, veering into the tragicomic, the melancholic, and even the depressing. Who or what, then, is the donkey? What distinguishes it and what makes it so difficult to pin down?

Teil I: Onos Lyras oder der Esel mit der Leier

Die Faszination mit dem Esel verfolgt mich seit geraumer Zeit. Und obwohl mich das Tier schon länger begleitet, oder ich es schon länger mit mir herumtrage, fällt es mir schwer, meinem Esel eine Silhouette zu geben, ihn in Stellung zu bringen, zu positionieren. Die viel beschworene Sturheit des Esels kommt in den Sinn und ein ausgestopfter Esel betritt die Bühne, doch dazu später mehr. Sicher ist, soviel sei an dieser Stelle bereits verraten, dass sich der Esel als ein recht komplexer und widerständiger Begleiter erweisen wird. Mehr noch: Er rückt in eine gewisse Nähe zum Trickster, zum Tragikomischen und zur Melancholie oder Depression. Wer oder was ist also der Esel? Was zeichnet ihn aus und was macht es so schwer, ihn zu fassen?

Let’s begin with the most persistent attribute of the donkey—its stubbornness. This can be explained by evolutionary biology: unlike horses, donkeys do not flee from predators. In the rugged desert borderlands of northern Africa, the donkey’s original home, an overly hasty attempt to flee through the boulder-strewn and rocky desert wastes posed a greater threat than directly facing up to an attacker. Against this backdrop, the donkey’s obstinacy appears as neither indifference nor stupidity, but instead as a survival mechanism that is necessarily oriented to its given environment. Nonetheless, the donkey usually seems to get in the way, for better or for worse, both for itself as well as for us.1

Beginnen wir mit der hartnäckigsten Zuschreibung des Esels – seiner Sturheit. Für diese gibt es eine evolutionsbiologische Erklärung: Im Gegensatz zu Pferden sind Esel keine Fluchttiere. In den schroffen Wüstengrenzregionen Nordostafrikas, der ursprünglichen Heimat des Esels, wäre die überhastete Flucht durch Geröll- und Steinwüsten gefährlicher als sich einer Bedrohung zu stellen. Der Starrsinn des Esels ist vor diesem Hintergrund weder Gleichgültigkeit noch Dummheit, sondern ein Überlebensmechanismus, der sich notwendigerweise an den gegebenen Umweltbedingungen ausrichtet. Nichtsdestotrotz steht der Esel meist im Weg, zum Guten und zum Schlechten für uns und für ihn selbst.1

During more than 5000 years of shared cultural history between donkey and human, our long-eared companion with large dark eyes, long lashes, and full lips has accumulated a seemingly very diverse repertoire of ascriptions, attributes, and associations. And although the economic significance of the donkey as a beast of burden has greatly diminished in industrialized societies, it appears as if the donkey—and above all its braying—has long since been seared into the cultural memory. Music theorist and passionate donkey historian Martin Vogel, whose 1973 work Onos Lyras, or: The Donkey with the Lyre is an impressive testimony to the animal, places our long-eared companion at the center of early cultural history, whose origin he locates in the culture of nomadic desert peoples: the Persian, Hebrew, and Sumerian “Donkey Men”. Also of central importance to Vogel’s study are the three descendants of Cain, especially Jubal, the biblical “inventor of music”. Two other equally important inventions are also attributed to his brothers, Jabal and Tubal-cain, who are described as the forefathers of nomadic living and the first blacksmiths respectively. Vogel sees the donkey as the link between these three accomplishments, as well as their actual catalyst, concluding that it was the donkey breeders who were constantly advancing into new territories as itinerant shepherds, blacksmiths, and musicians. Unassuming, sure-footed, with no fear of heights, the donkey thus opened up not only new places but new ways of life to these tribes, long before the domestication of the horse or camel. It is thus not particularly surprising, Vogel goes on to argue, that the donkey had a decisive impact on these peoples’ thoughts, actions, and even religious beliefs. Following this line of thought, the origins of pre-Christian donkey worship form an additional focal point for Vogel’s research, along with the prevalence of donkey deities in antiquity, from the ancient Egyptian god Set right through to Yahweh, whose name the donkey’s cry supposedly echoes.2

In über 5000 Jahren gemeinsamer Kulturgeschichte von Esel und Mensch hat unser langohriger Begleiter mit den großen dunklen Augen, langen Wimpern und vollen Lippen insgesamt ein sehr heterogen anmutendes Repertoire an Besetzungen, Zuschreibungen und Assoziationen angesammelt. Und wenngleich die wirtschaftliche Bedeutung des Esels als Lasttier in den Industriegesellschaften stark rückläufig ist, scheint es so, als habe sich der Esel und allen voran sein Schrei schon längst in das kulturelle Gedächtnis eingebrannt. Der Musiktheoretiker und passionierte Eselhistoriker Martin Vogel, der dem Langohr in Onos Lyras: Der Esel mit der Leier (1973) ein beeindruckendes Zeugnis ausstellt, rückt unseren Begleiter gar ins Zentrum der frühzeitlichen Kulturgeschichte, deren Wiege er in der Kultur nomadischer Wüstenvölker, den persischen, hebräischen und sumerischen “Eselmännern”, ausmacht. Im Zentrum von Vogels Untersuchung stehen dabei die drei Abkömmlinge des Kain, insbesondere Jubal, der biblische Urvater der Musik. Seinen Brüdern Jabal und Tubalkain werden zwei ebenso wichtige Erfindungen zugeschrieben: die nomadische Lebensweise und die Metallverarbeitung. Im Esel sieht Martin Vogel das Bindeglied und den eigentlichen Katalysator dieser drei Errungenschaften und kommt zu dem Schluss, dass es die Eselzüchter*innen waren, die als Wanderhirt*innen, Wanderschmied*innen und Wandermusiker*innen in immer neue Gebiete vorstießen. Lange vor der Domestizierung von Pferd und Kamel erschloss der genügsame, trittsichere und schwindelfreie Esel jenen Stämmen dabei nicht nur neue Orte, sondern auch Lebensformen. Folgt man der Argumentation des Autors ist es daher nicht allzu verwunderlich, dass der Esel das Denken, Handeln und sogar den Glauben dieser Menschen bestimmte. Vor diesem Hintergrund liegt ein weiterer Fokus von Vogels Recherche auf den Ursprüngen vorchristlicher Eselkulte sowie den weit verbreiteten Eselgottheiten des Altertums vom altägyptischen Gott Seth bis hin zu Jahwe, in dessen Name gar der Schrei des Tieres nachklingen soll.2

In actual fact, the donkey’s cry has always been considered an expression of strength, and although the donkey has always been a beast of burden—one subjected to whippings and mistreatment—the donkey of antiquity is described an animal so bristling with power and courage that it was sometimes capable of frightening off bears and wolves. The donkey was equally considered an erotic and fertile animal, possessed of an incredible virility, its cry an expression of ecstatic lust. Here it is worth briefly calling to mind the astounding and multi-faceted cry of the donkey, which among other associations is reminiscent of squeaking water-pumps, dog-barks, human groans, and the screeches of chimpanzees.3 In his 1909 work Die antike Tierwelt (The Animals of the Ancients), Otto Keller writes:

Tatsächlich galt der Schrei des Esels seit jeher als Ausdruck der Stärke und wenngleich der Esel immer auch Arbeitstier war, immer auch Gepeitschter und Geschundener, so ist der Esel der Antike als ein von Kraft und Neugier nur so strotzendes Tier überliefert, das mitunter Bären und Wölfe in die Flucht schlägt. Ebenso galt der Esel als erotisches beziehungsweise geiles Tier, als Träger einer unerhörten Potenz, sein Schrei als Ausdruck ekstatischer Lust. Hier lohnt es, sich den ganz erstaunlichen und facettenreichen Schrei des Esels kurz ins Gedächtnis zu rufen, der neben weiteren Assoziationen an quietschende Wasserpumpen, Hundebellen, menschliches Stöhnen und die Laute von Gibbon-Affen erinnert.3 Otto Keller schreibt in Die antike Tierwelt (1909):

Sound: Donkey sounds from APPENDIX (2020) by Lukas Ludwig.

The wild donkey, along with the tame domesticated donkey of inner Asia Minor, were characterized by gaiety, swiftness, and prodigality, and were consequently the perfect animal for the love-stricken and rapturous Dionysus and his retinue of Silenus and satyrs, who just like the characters of our carnival fanfare illustrate the indelible desire of humans to take a full draught now and then from the cup of unabashed cheer, exuberance, and sensual pleasure.4

“Der wilde Esel und auch der einheimische zahme Esel des inneren Kleinasiens zeichneten sich aus durch Lustigkeit, Schnelligkeit, Üppigkeit und waren sonach das richtige Tier für den liebestollen rauschliebenden Dionysos und sein Gefolge von Silenen und Satyrn, die ja doch gleich unserem Fastnachtsrummel das untilgbare Bedürfnis des Menschen illustrieren, dann und wann wieder einen vollen Zug aus dem Becher des ungenierten Frohsinns, der Ausgelassenheit, der Sinnenlust zum Munde zu führen.”4

The donkey as the heraldic animal of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, pleasure, fertility, and insanity—who would have thought?

Der Esel als Wappentier des Dionysos, des griechischen Gott des Weines, der Freude, der Fruchtbarkeit und des Wahnsinns—wer hätte das gedacht?

EN: Lucius takes human form. Illustration from a 1345 edition of the Metamorphoses now housed in the Vatican Library in Rome.

DE: Lucius nimmt menschliche Form an. Illustration einer Ausgabe der Metamorphosen von 1345, die sich heute in der Vatikanischen Apostolischen Bibliothek in Rom befindet.

A peach coloured ocular shape encompasses the image. Inside of it an emaciated person with long flowing hair leans over into thinly painted lines that resemble the tentacles of a squid, with its eye looking down at the human bowing before it. A crescent below and above edge the circle. Outside of the confines of the circle are ochre-finished brush strokes invoking textures of dried grass.

A further example of how the donkey was perceived in antiquity can be found in Apuleius’ novel The Golden Ass (170 AD), which first appeared under the title Metamorphoses, alluding to the work by Ovid. Apuleius adapted the story from a Greek satirist named Lucian, augmenting it with an array of supplementary stories, including that of Cupid and Psyche, and introducing an incredibly modern first-person narrator in the form of Lucius. The driving force of the narrative is the protagonist’s curiosity and appetite for risk; fascinated by the dark arts of the sorceress Pamphile, Lucian attempts a failed spell which results in him being turned into a donkey. In donkey form, he subsequently ventures forth on a kind of satirical road trip, encountering robber bandits, slaves, androgynous begging monks, tragic lovers, and a zoophilic benefactress. Ultimately growing weary of his existence and with little hope for his salvation, Lucius offers a prayer to mother goddess Isis, who returns him to human form. Impressed by the goddess’s power and eager to be initiated into the secrets of her power, the transformed figure undergoes a process of purification and henceforth lives as a high priest of an Isis cult in Rome.

Eine weitere Überlieferung des antiken Eselbildes findet sich in Apuleius’ Eselroman Der Goldene Esel (170 n.Chr.), der in Anlehnung an das literarische Werk Ovids zunächst unter dem Titel Metamorphosen erschien. Den literarischen Stoff übernimmt Apuleius von dem griechischen Satiriker Lukian, erweitert die Vorlage allerdings um eine Reihe von Nebenerzählungen, darunter die Geschichte von Amor und Psyche und führt mit dem Protagonisten Lucius einen erstaunlich modernen Ich-Erzähler ein. Die treibende Kraft der Erzählung ist die Neugier und Risikobereitschaft des Protagonisten, der fasziniert von den dunklen Künsten der Zauberin Pamphile in Folge eines schiefgegangenen Zaubers in einen Esel verwandelt wird. In Eselgestalt erlebt er eine Art satirischen Roadtrip zwischen Räuberbanden, Versklavung, androgynen Bettelmönchen, tragisch Verliebten und einer Liaison mit einer zoophilen Gönnerin. Seines Schicksals schließlich überdrüssig und ohne Hoffnung auf Erlösung ruft Lucius die Muttergöttin Isis an, die seine ursprüngliche Gestalt wiederherstellt. Beeindruckt von der Macht der Göttin und begierig darauf, in die Geheimnisse ihrer Macht eingeweiht zu werden, durchläuft der Zurückverwandelte einen Läuterungsprozess und lebt fortan als Hohepriester eines römischen Isiskults.

Although the novel is obviously designed to entertain—the prologue, for example, ends with the words “Give me your ear, reader: you will enjoy yourself.”5—at the same time it articulates a very serious interest in the abysmal and the marginalized, in violence and the societal periphery. In the course of the story, the donkeyfied Lucius seems permanently torn between curious astonishment, amusement, and dismay at the fateful turmoil and human cruelty that only appears to become fully apparent to him after his transformation. It is perhaps worth highlighting that the protagonist’s attributes, in particular his curiosity, thirst for action, and roguelike nature, correspond with those ascribed to the donkey in antiquity.

Der Roman ist durchaus als unterhaltende Prosa angelegt – der Prolog etwa endet mit den Worten “Jetzt beginnt es. Merke auf [Leser*in], es wird etwas zu lachen geben.”5—entwickelt jedoch gleichzeitig ein sehr ernsthaftes Interesse am Abgründigen und Randständigen, an Gewalt und der gesellschaftlichen Peripherie. Der zum Esel verwandelte Lucius scheint dabei permanent hin- und hergerissen zwischen neugierigem Staunen, Belustigung und Entsetzen über die schicksalhaften Wirren und menschlichen Grausamkeiten, die sich dem Verwandelten erst in Eselgestalt vollständig zu eröffnen scheinen. Die Attribute des Protagonisten, allen voran seine Neugier, sein Tatendrang ebenso wie seine Spitzbübigkeit, decken sich dabei mit den antiken Zuschreibungen des Esels.

Sound: Eric I from APPENDIX (2020) by Lukas Ludwig.

EN: Donkeys in Entrepierres, France.

DE: Esel in Entrepierres, Frankreich

Two donkeys, side by side leaned over grazing. Their faces are touching, making it seem as if they are reaching for the same blade of grass. Behind them a blurry background of a grey countryside.

With the emergence of Christianity, the figure of the donkey experienced a momentous reinterpretation, becoming taciturn and essentially silent. If it spoke at all, it was as a messenger of a higher power. Its virility, erotic power, and curiosity fell victim to a subservient introversion. But even Christianity was unable to entirely do without the donkey, and so it became the pacifist servant of its savior Jesus Christ, who rode into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday on a female donkey’s back. In recognition of its good service to Christianity, so the story goes, the donkey was rewarded with a special symbol: a cross-shaped coat pattern across its back and shoulders, the so-called cross stripe or dorsal stripe. As a pacifist anti-war horse, the donkey was from then on endowed with a stoic calm and monastically silent manner. As a born bearer of heavy burdens and great pains it comes closer to the company of martyrs and ascetic mystics—a connection that we will encounter again at a later stage.

Mit dem Auftauchen des Christentums erfährt der Esel eine folgenreiche Umdeutung, er wird wortkarg und stumm. Wenn überhaupt spricht er als Botschafter einer höheren Macht. Seine Potenz, erotische Kraft und Neugier fallen einer unterwürfigen Introvertiertheit zum Opfer. Doch auch das Christentum kann nicht auf den Esel verzichten und so wird er zum pazifistischen Diener und Reittier des Erlösers Jesus Christus, der am Palmsonntag auf dem Rücken einer Eselstute nach Jerusalem einreitet. Im Anschluss an seinen guten Dienst am Christentum, so die Geschichte, wurde dem Esel eine symbolische Auszeichnung verliehen: eine kreuzförmige Fellzeichnung auf Rücken und Schultern, der sogenannte Kreuz- oder Aalstrich. Als pazifistisches Anti-Schlachtross ist der Esel fortan mit einer stoischen Ruhe und mönchischen Schweigsamkeit ausgestattet. Als geborener Träger großer Lasten und Schmerzen rückt er in die Nähe der Märtyrer*innen und asketischen Mystiker*innen—ein Bezug, der uns an anderer Stelle erneut begegnen wird.

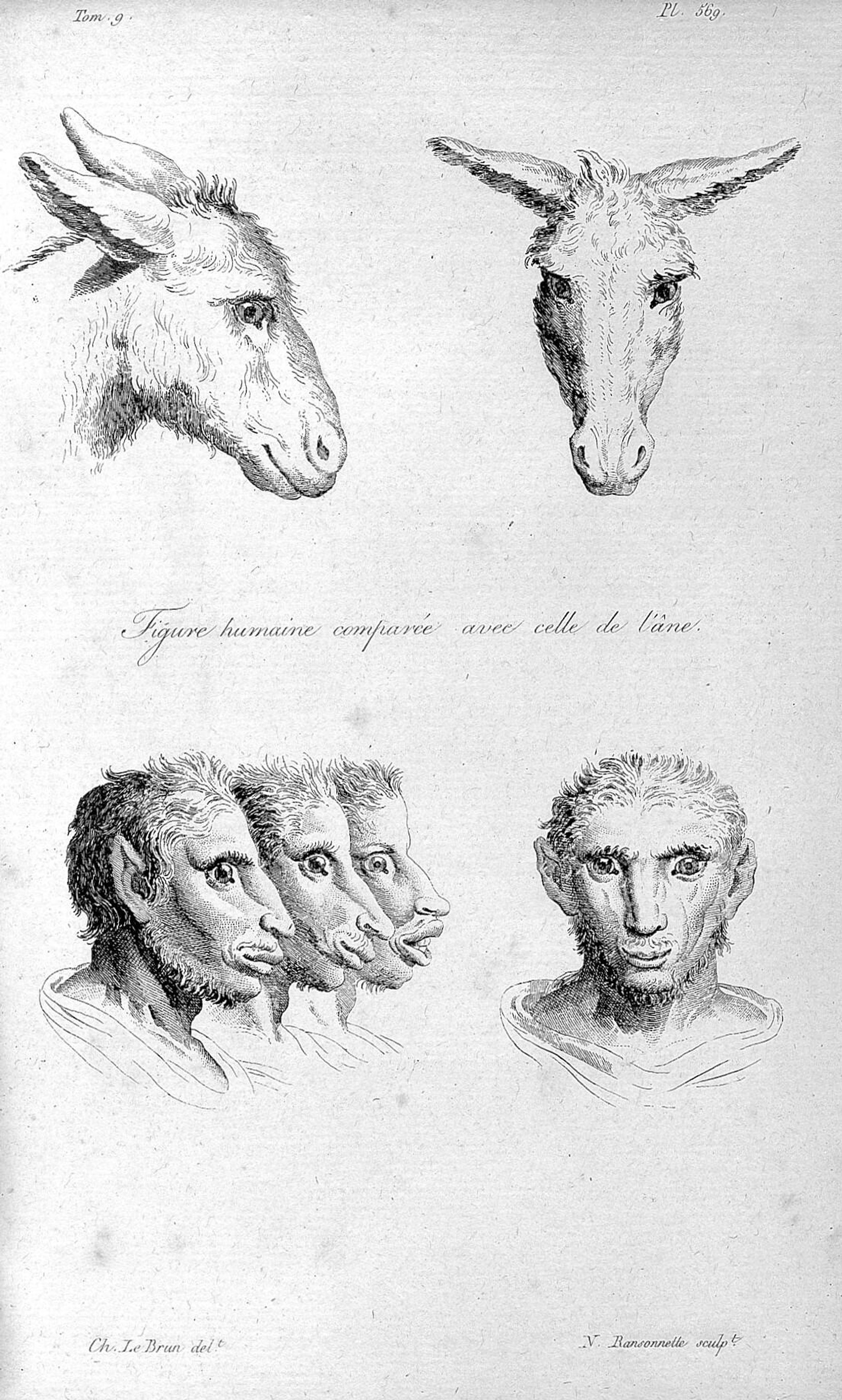

EN: Copperplate engraving after B. Porta. Appears in Johann Caspar Lavater, Physiognomische Fragmente (Physiognomic Fragments), Leipzig 1775.

DE: Kupferstich nach B. Porta. Erschienen in: Johann Caspar Lavater, Physiognomische Fragmente, Leipzig 1775.

A copperplate engraving with four illustrations, two on the top and two underneath. The first is a side view of a donkey’s head, and the second is the front view. The illustration on the bottom left is the side view of what appears to be a man transforming into a donkey - three frames of his face show different variations of the transformation. His cheekbones and nose elongate, his eyes become more animal-like, and his beard and hair thin out and become fur. The final illustration is a front view of the transformed man. Between the top and bottom images is the text “Figure humaine comparée avec celle de l'âne.”

The responsibility for the donkey being ascribed the attribute of devoted stupidity ultimately lies at the feet of physiognomy, the pseudoscientific linking of physiological features with psychological character traits whose inglorious history stretches from antiquity through to the era of algorithm-based facial recognition. According to this practice, this image is only reinforced by their long, flexible ears and flat forehead. In this respect the donkey receives the same treatment as most other herbivores, who all tend to be presented as goofy, narrow minded and weak due to their gentleness, as though they required leadership by a sovereign. As problematic as the physiognomists’ schematization of animals may be, their images do present the topos of the transformation from human to animal and animal to human once again—the metamorphosis perpetuates itself.6

Die Physiognomik, also die pseudowissenschaftliche Verkettung von physiologischen Merkmalen mit psychologischen Charakterzügen, deren unrühmliche Geschichte von der Antike bis in Zeiten algorithmischer Gesichtserkennung reicht, ist schließlich für die Zuschreibung der devoten Dummheit des Esels verantwortlich. Dabei wurden ihm vor allem seine langen flexiblen Ohren und die flache Stirn zum Verhängnis. Dem Esel geht es damit nicht anders als den meisten Pflanzenfressern, die ihrer Sanftheit wegen alle etwas vertrottelt, kleingeistig und schwach dargestellt werden, ganz so, als ob sie der Führung durch einen Souverän bedürften. So problematisch die Tierschemata der Physiognomiker*innen auch sein mögen, so eröffnen die Bilder einmal mehr den Topos der Verwandlung von Mensch zu Tier und Tier zu Mensch—die Metamorphose schreibt sich fort.6

In the end, the physiognomic attributes of stupidity and subservience only end up partly sticking to the figure of the donkey, and despite—or perhaps precisely because of—the drastic change in how it was reinterpreted and reassigned a role by Christianity, there have subsequently been a number of anachronistic and subversive forms of onolatry, or donkey worship, practiced around the world that express the ambivalence of donkey-related imagery and metaphor. In keeping with the tradition of The Golden Ass, donkey figures in literature repeatedly stray from the beaten path of bourgeois society. Donkey figures are frequently portrayed as having artistic leanings, although this aptitude is often expressed covertly or in an ironically refracted manner. Author Jutta Person, whose 2013 book Esel: Ein Portrait (Donkey: A Portrait) is a wonderfully compact cultural history of the donkey, draws attention to a literary Onos Lyras that many would likely be familiar with: the donkey of the “Town Musicians of Bremen”, who after a lifetime of hard work runs away from its master to make a living as a lyre player in the city of Bremen. Not at all submissive, in a conversation with an aging guard-dog it comes to the following conclusion: “You can find something better than death anywhere.”7

Letztlich bleiben auch die Zuschreibungen der Physiognomik, also die Dummheit und Unterwürfigkeit des Esels, nur teilweise an ihm haften und trotz oder vielleicht gerade aufgrund der drastischen Umdeutungen und Neubesetzungen finden sich quer durch die Epochen eine Vielzahl anachronistischer und subversiver Formen der Eselverehrung, die die Ambivalenz der Eselmetaphorik zum Ausdruck bringen. Ganz in der Tradition des Eselromans verlassen die literarischen Eselfiguren immer wieder die ausgetretenen Pfade der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft. Überhaupt wird dem Esel durchaus eine Anlage zum Musischen zugeschrieben, wenngleich sich diese Begabung oftmals versteckt oder ironisch gebrochen äußert. Die Autorin Jutta Person, die mit Esel. Ein Portrait (2013) eine wunderbar kompakte Kulturgeschichte des Esels vorgelegt hat, macht uns in diesem Kontext auf einen literarischen Onos Lyras aufmerksam, den Esel der Bremer Stadtmusikanten, der nach langen Jahren der Arbeit den Hof seines Herren verlässt, um fortan als leierspielender Bremer Stadtmusikant seinen Lebensunterhalt zu bestreiten. So gar nicht devot kommt er im Gespräch mit einem alternden Wachhund zu folgendem Schluss: “Etwas besseres als den Tod findest du überall.”7

The emancipatory power embodied by the donkey is also paralleled in the medieval Feast of the Ass, a kind of carnival with religious, humorous, and erotic elements that was a fixture of the liturgical calendar through to the High Middle Ages. In the transcript of a radio program produced for Süddeutsche Rundfunk entitled Feasts of the Ass and of Fools: Medieval Music between the Church and Heresy, Wolfgang Lempfrid quotes from an unidentified historical source that details the proceedings of a Feast of the Ass:

Die emanzipatorische Kraft, die im Esel steckt, findet auch Entsprechung in den mittelalterlichen Eselmessen, einer Art Karnevalsveranstaltung mit religiösen, humorvollen und erotischen Aspekten, die bis ins Hochmittelalter fester Bestandteil des liturgischen Kalenders waren. Im Sendemanuskript eines Radiobeitrags des Süddeutschen Rundfunks mit dem Titel Von Narren- und Eselsfesten. Mittelalterliche Musik zwischen Kirche und Ketzerei zitiert Wolfgang Lempfrid eine nicht näher bezeichnete historische Quelle zum Ablauf eines Eselsfests:

The “false bishop” holds a festive service in the morning: as he gives the blessing, the remaining clergy dance around the sanctuary singing obscene songs dressed mostly as prostitutes, pimps, or musicians. When at the altar, the subdeacons eat sausages during the service and play dice and card games during the transfiguration ceremony. One of them substitutes the frankincense normally burnt in the censer for old shoe-soles and excrement in an attempt to overpower the priest reading the sermon with the stench. Service-books are held upside-down and rather than sing psalms and liturgical songs, the clergy instead mutter gibberish or impersonate livestock.8

“Der Narrenbischof hält in der Früh einen feierlichen Gottesdienst und spricht den Segen, während die übrigen Geistlichen, meist als Dirnen, Kuppler oder Musikanten verkleidet, im Chorraum tanzen und springen und zotige Lieder singen. Die Subdiakone verzehren auf dem Altar Würste, und während der Wandlung spielen sie mit Karten und Würfeln. Einer legt ins Rauchfaß statt Weihrauch Stücke von alten Schuhsohlen und Exkremente, damit dem Messe-lesenden Priester der Gestank in die Nase steige. Sie halten die Bücher verkehrt und singen keine Psalmen und liturgische Gesänge, sondern murmeln unverständliche Worte oder blöken lautstark wie das Vieh.”8

It would be far too easy to see the livestock mentioned here as a metaphor for devoted stupidity or even subservience. Bearing a certain resemblance to the topos of the medieval death dance, these Feasts of the Ass appear as expressions of a kind of excess of vitality. What is invoked and adored in the donkey is here associated with a sinister corporeal force, an insistence of something non-verbal that counters the liturgy with nonsensical murmuring, ecstasy, and frenzy. Ultimately, there seems little to distinguish the donkey’s cap from the fool’s. Like the fool, whose outsider status at court makes him a tragicomic figure and the holder of ominous knowledge conveyed in a language existing at the edge of language and the edge of society, so the figure of the donkey has a peculiar solitariness about it—at least when in the company of humans.

Es wäre wohl zu einfach, das Vieh hier als Metapher devoter Dummheit oder gar Unterwürfigkeit einzusetzen. In einer gewissen Nähe zum Topos des mittelalterlichen Totentanzes kommt in den Eselsmessen eher eine Art Überschuss an Lebendigkeit zum Vorschein. Was im Esel aufgerufen und angebetet wird, steht erneut in Verbindung mit einer unheimlichen körperlichen Kraft, einer Insistenz eines Nichtsprachlichen, das der Liturgie das unsinnige Gemurmel, die Ekstase und den Rausch entgegensetzt. Schließlich ist auch der Sprung von der Esel- zur Narrenkappe nicht weit. Wie der Narr, dessen Außenseitertum am Hofe ihn zur tragikomischen Figur und zum Träger eines unheilvollen Wissens macht, vermittelt durch eine Sprache am Rand der Sprache und am Rand der Gesellschaft, haftet auch dem Esel eine sonderbare Einsamkeit an, zumindest wenn er unter Menschen ist.

In general, it seems that the cultural-historical images of the donkey tend to start transforming into their opposites almost as immediately as they appear: virility and devotion, critique and affirmation, activity and passivity, language and corporeality appear here as unavoidably encroaching upon and connected with one another, in the sense of a game or an exchange of physical and psychic forces. In subsequent sections of this text the donkey is positioned in an interstitial space, a site of instability with respect to linguistic reference. Here, the donkey’s stubbornness presents itself as a kind of desire, a delight in the deterioration of the symbolic, of the implicit ordering of discourse, power, and the law. The donkey’s desire appears as a desire for the acceleration of conceptual transitions, for the destruction of conceptual opposition and thereby ultimately of meaning.

Generell lässt sich festhalten, dass die kulturhistorischen Eselbilder dazu tendieren, sich im Vollzug in ihr Gegenteil zu verkehren. Potenz und Devotion, Kritik und Affirmation, Aktivität und Passivität, Sprache und Leiblichkeit erscheinen hier unweigerlich übergriffig und miteinander verknüpft im Sinne eines Spiels oder Austauschs physischer und psychischer Kräfte. Im weiteren Verlauf dieses Textes stellt sich der Esel in einen Zwischenraum, einen Ort der Instabilität sprachlichen Bezugs. Die Sturheit des Esels eröffnet sich hier ebensosehr als eine Lust, ein Genießen am Verfall des Symbolischen: der impliziten Ordnung der Diskurse, der Macht und des Gesetzes. Die Lust des Esels erscheint als eine Lust an der Beschleunigung begrifflicher Übergänge, an der Zerstörung von begrifflicher Opposition und damit letztlich von Sinn.

Sound: Dummer, schöner Schwan from APPENDIX (2020) by Lukas Ludwig.

Part II: Eeyore’s Poem

Teil II: Eeyore’s Poem

EN: Group of stuffed animals that Alan Alexander Milne purchased for his son Christopher Robin Milne in 1921. Clockwise from bottom left: Tigger, Kanga, Edward Bear (Winnie-the-Pooh), Eeyore, and Piglet.

DE: Gruppe von Stofftieren die Alan Alexander Milne 1921 für seinen Sohn Christopher Robin Milne erwarb. Im Uhrzeigersinn von unten links: Tigger, Kanga, Edward Bear (Winnie-the-Pooh), Eeyore und Piglet.

A stuffed tiger, kangaroo, bear and donkey sit atop a green table reading books that are laid open for them. Behind them is a library, with many books on shelves, and a blue recycling bin.

Back to the beginning of this text: what could that mean, to give shape to my donkey, to endow it with substance? Up until this point we have primarily observed the donkey as a cultural-historical or literary vessel. When the donkey speaks, a human speaks, a subject. When it speaks, it tells a story, a biography. In doing so, however, it becomes evident—particularly in the example of Lucius—that the donkey’s coat is more than just a costume, a fantastical construct housing an authentic inner character: this costume is always wholly complete, is itself a metamorphosis, a transformation. If we accept this, then a certain stuffed donkey comes to mind, one whose inner character ultimately does not manifest as an I, but rather as stuffing that has been given form: illegible, inexplicable, and vulgar.

Zurück zum Anfang dieses Textes: Was könnte das bedeuten, meinem Esel eine Silhouette geben, ihm eine Haut zu geben? Bis jetzt haben wir den Esel vor allem als ein kulturhistorisches beziehungsweise literarisches Gefäß betrachtet. Wenn der Esel spricht, spricht ein Mensch, ein Subjekt. Wenn er spricht, dann erzählt er eine Geschichte, eine Biografie. Dabei zeigt sich allerdings gerade am Beispiel des Lucius, dass die Hülle des Esels nicht nur eine Verkleidung, ein fantasievolles Konstrukt ist, das ein wahrhaftiges Inneres beherbergt—die Verkleidung ist immer vollständig, ist Metamorphose, ist Verwandlung. Wenn wir dies akzeptieren, kommt ein ausgestopfter Esel in den Sinn, dessen Inneres sich letztlich nicht als ein Ich offenbart, sondern als in Form gebrachtes Füllmaterial: unlesbar, unerklärbar, vulgär.

The donkey in question is of course Eeyore, from A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh. In the Hundred-Acre Wood, the fictional universe in which the stories are set, the bear lives as part of a community of (stuffed) animals. These include Piglet, a stuttering piglet with signs of an anxiety disorder; Tigger, a hyperactive tiger; Kanga, a mother kangaroo, and her joey Roo; the snobbish Owl; Rabbit, whose tough exterior belies a soft heart; and finally Eeyore, a lovable albeit melancholy and depressed donkey. The group is accompanied on their adventures by Christopher Robin, a boy who lives at the edge of the Hundred-Acre Wood and the fictional equivalent of the author’s son of the same name, for whom the stories were first written. Milne’s son would later accuse his father of exploiting his childhood for literary gain.9

Der Esel, von dem hier die Rede ist, ist Eeyore aus Alan Alexander Milnes Kinderbuchreihe Winnie-the-Pooh. Im Hundert-Morgen-Wald, dem literarischen Universum Winnie-the-Poohs, wohnt der Bär als Teil einer Gemeinschaft von (Stoff-)Tieren. Darunter finden sich Piglet, ein stotterndes Ferkel mit Anzeichen einer Angststörung; Tigger, ein hyperaktiver Tiger; die Kängurumutter Kanga mit ihrem Jungen Roo; Owl, eine versnobte Eule; Rabbit, ein Kaninchen mit harter Schale, aber weichem Kern und schließlich Eeyore, ein liebenswürdiger, wenngleich melancholisch-depressiver Esel. Begleitet wird die Gruppe von Christopher Robin, einem Jungen, der am Rand des Hundert-Morgen-Walds lebt und als literarische Figur an A. A. Milnes gleichnamigen Sohn angelehnt ist, dem ursprünglichen Adressaten der Geschichte. Milnes Sohn wird seinem Vater später vorwerfen, seine Kindheit zugunsten dessen literarischen Werks ausgeschlachtet zu haben.9

Eeyore is a donkey whose tail falls off. More precisely, it is not clear whether his tail is actually a part of him or was always a later addition. Eeyore frequently loses his makeshift tail in the animated adaptation of the series, meaning that Christopher Robin must repeatedly re-attach it with the help of a nail. This recalls the children’s game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey”, in which players try to accurately pin a tail or tails to a picture of a donkey while blindfolded.

Eeyore ist ein Esel, dem der Schwanz abfällt. Genauer gesagt ist nicht sicher, ob der Schwanz überhaupt Teil des Esels oder immer schon nachträglich angebracht ist. Eeyore verliert den eher notdürftig fixierten Schwanz in mehreren Episoden der Zeichentrickadaption des Kinderbuchs, sodass er immer wieder von Christopher Robin mithilfe eines Nagels befestigt werden muss. Wir erinnern uns an das Kinderspiel Pin the tail on the donkey, zu deutsch: Eselschwanz, bei dem die Spieler*innen mit verbundenen Augen einem Eselbild seinen Schwanz beziehungsweise seine Schwänze anheften müssen. Ziel des Spiels ist es, den Schwanz an die richtige Stelle zu setzen.

EN: Pin the Tail on the Donkey.

DE: Eselschwanz

A picture of a pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey bathed in orange light. The donkey is surrounded by multi-coloured balloons.

The literary universe of Winnie-the-Pooh is generally suffused with a lightly melancholic or at least nostalgic atmosphere. This atmosphere is in the first instance connected to the context in which the texts were created: Milne uses the writing of his children’s books to work through his experiences of the first world war, above all the question of humans’ capacity to act in the face of historical catastrophe.10 Secondly, Winnie-the-Pooh is an examination of the topoi of childhood and growing up as well as the related loss of a retrospectively imagined innocence. In psychoanalytic terms, this involves the conception of an unbroken identity perceived as absolute, a pre-subjective refuge of impersonal longing in which the linguistically mediated separation between subject and object has not yet taken place. Although the Hundred-Acre Wood remains to some extent intact as a fantasy universe, Christopher Robin does age over the course of the stories, and eventually bids farewell to the group in order to attend boarding school. In this sense, Winnie-the-Pooh can also be read as a story of alienation.

Dem literarischen Stoff des Winnie-the-Pooh Universums unterliegt generell eine leicht melancholische oder zumindest nostalgische Atmosphäre. Diese Atmosphäre hat zum einen mit dem Entstehungskontext des literarischen Stoffs zu tun, so verarbeitet Milne in den Kinderbüchern seine Erfahrungen während des ersten Weltkriegs, vor allem auch die Frage menschlicher Handlungsfähigkeit angesichts der historischen Katastrophe.10 Zum anderen ist Winnie-the-Pooh eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem Topos der Kindheit und des Aufwachsens sowie des damit verbundenen Verlusts einer retrospektiv imaginierten Unschuld. Psychoanalytisch formuliert geht es dabei um die Vorstellung einer als absolute wahrgenommenen, unversehrten Identität, ein vor-subjektiver Hort unpersönlicher Sehnsucht, in der die über die Sprache vermittelte Trennung zwischen Subjekt und Objekt nicht stattgefunden hat. Während der Hundert-Morgen-Wald als Fantasieuniversum gewissermaßen intakt bleibt, altert Christopher Robin über den Verlauf der Geschichten und nimmt schließlich Abschied von der Gruppe, um ein Internat zu besuchen. Winnie-the-Pooh lässt sich insofern auch als Geschichte einer Entfremdung lesen.

The donkey Eeyore embodies this longing. He likewise embodies a kind of disavowal of this alienation, which brings us closer to the esoteric enjoyment of the instability of the symbolic order. Here I would like to quote a brief exchange from Winnie-the-Pooh and a Day for Eeyore (1983) which illustrates this relation. To briefly summarize the plot of this 25-minute TV adaptation: at the beginning of the episode, Eeyore seems to be more melancholy than usual. It turns out that it is Eeyore’s birthday, but nobody has noticed; eventually, the animals get together and throw him a surprise birthday party. At the beginning of the episode, the following exchange occurs between Winnie-the-Pooh and Eeyore:

Der Esel Eeyore verkörpert diese Sehnsucht. Er verkörpert gleichermaßen eine Art Verleugnung der Entfremdung, die uns näher an das abseitige Genießen an der Instabilität des Symbolischen bringt. Ich zitiere an dieser Stelle einen kurzen Dialog aus Winnie-the-Pooh and a Day for Eeyore (1983), der dieses Verhältnis verdeutlicht. Um die Handlung der 25-minütigen TV-Adaption grob zusammenzufassen: Eeyore scheint zu Beginn der Folge noch melancholischer zu sein als gewöhnlich. Es stellt sich heraus, dass der Esel Geburtstag hat und schließlich finden sich die Tiere zu einem improvisierten Geburtstagsbankett zusammen. Zu Beginn der Episode ergibt sich folgender Austausch zwischen Winnie-the-Pooh und Eeyore:

Sound: Eeyore from APPENDIX (2020) by Lukas Ludwig.

Pooh: Eeyore, what’s the matter?

Eeyore: What makes you think anything’s the matter?11

Pooh: Eeyore, was ist los?

Eeyore: Warum glaubst du, das irgendetwas los ist?11

Taking a somewhat free interpretation of Eeyore’s response, we could re-fashion it into a more radical question: “What makes you think there is anything at all that could matter?” Earlier in this text, we remarked that the donkey’s rage is directed at language and meaning, at the placing of the subject into a meaningful, historical, or autobiographical relation. While Pooh assumes that Eeyore will be able to locate a reason or an object of his misery, a concrete lack or misfortune, Eeyore responds with an almost aggressive—if monotonously expressed—question of his own, one which Pooh naturally cannot understand, let alone answer; in short, a kind of nihilistic leap of faith.12 Eeyore is not missing anything in particular, nor has he experienced concrete misfortune; it is not the lack of a birthday present that has determined the low mood to which he has succumbed in every sense. What is missing is nothing less than a confidence in the integrity of language, the integrity of the symbolic order as a productive conceptual sequence that, functioning as a guarantor of desire and aversion, would structure the subjective perception of the world and in turn enable one’s meaningful inscription within it. The donkey who lacks purpose, who is no longer capable of designating the objects of his world, appears as a result to have been deprived of the objects themselves. He flounders at the prospect of cathexis, of the relationships between subject and object that confer meaning, on the basis of which we affirm our own existence. The donkey’s enjoyment is therefore concentrated on a loss, a disavowal of the separation between subject and object, between a “me” and the objects of the world, between interior and exterior. It is thus a paradoxical enjoyment, for the deterioration of the symbolic order is always accompanied with the deterioration of the self.

In einer etwas freieren Übersetzung lässt sich Eeyores Erwiderung zu einer radikaleren Frage zuspitzen: “Was lässt dich glauben, dass es überhaupt etwas [matter] gibt, das Bedeutung hat?” Wir hatten an anderer Stelle bereits bemerkt, dass sich die Wut des Esels gegen die Sprache und Bedeutung, in anderen Worten gegen die Einschreibung des Subjekts in einen sinnhaften, historischen oder autobiografischen Zusammenhang richtet. Während Pooh davon ausgeht, dass Eeyore einen Grund, ein Objekt (“matter”) seines Trübsals identifizieren kann, einen konkreten Verlust, ein Unglück, reagiert Eeyore mit einer geradezu angriffslustigen, wenngleich monoton hervorgebrachten Gegenfrage, die der Bär selbstverständlich nicht verstehen, geschweige denn beantwortet kann—kurzum eine Art nihilistischer Leap of Faith, zu deutsch ein Sprung in den Glauben.12 Was Eeyore fehlt, ist nichts Bestimmtes, es ist ihm kein konkretes Unglück widerfahren, es ist nicht das fehlende Geburtstagsgeschenk, das entscheidend wäre für seine Stimmung, der sich der Esel mit allen seinen Sinnen hingibt. Was fehlt, ist nicht weniger als das Vertrauen in die Unversehrtheit der Sprache, die Unversehrtheit des Symbolischen als produktive Begriffskette, die als Garant von Lust und Unlust die subjektive Wahrnehmung der Welt strukturieren und eine sinnhafte Einschreibung in dieselbe ermöglichen würde. Der Esel ohne Sinn, der nicht länger in der Lage ist, die Objekte seiner Welt zu benennen, scheint dabei auch den Objekten selbst beraubt. Er scheitert an der Möglichkeit der Objektbesetzung, der sinngebenden Beziehungen zwischen Subjekt und Objekt, anhand derer wir uns unserer eigenen Existenz versichern. Das Genießen des Esels konzentriert sich alsdann auf einen Verlust, einer Verleugnung der Spaltung zwischen Subjekt und Objekt, zwischen mir und den Dingen in der Welt, zwischen dem Innen und dem Außen. Dabei handelt es sich um ein paradoxes Genießen, denn mit der Verfall des Symbolischen geht immer auch die Verfall des Selbst einher.

We previously labeled the donkey a trickster, a rake, and must point out at this juncture that this entails a kind of self-deceit, a deception of the self, a deception that exists outside social or ethical convention. What, then, is the donkey? Who—or more accurately, what—is doing the enjoying, if not the self?

Wir hatten den Esel vorhin einen Trickster genannt, einen Verführer, und müssen an dieser Stelle feststellen, dass es sich hierbei um eine Art Selbstbetrug handelt, einen Betrug des Selbst, einen Betrug außerhalb des Bereichs sozialer oder ethischer Konvention. Was ist der Esel also? Wer—oder besser gesagt was—genießt, wenn nicht das Selbst?

Sound: Lithic staircase from APPENDIX (2020) by Lukas Ludwig.

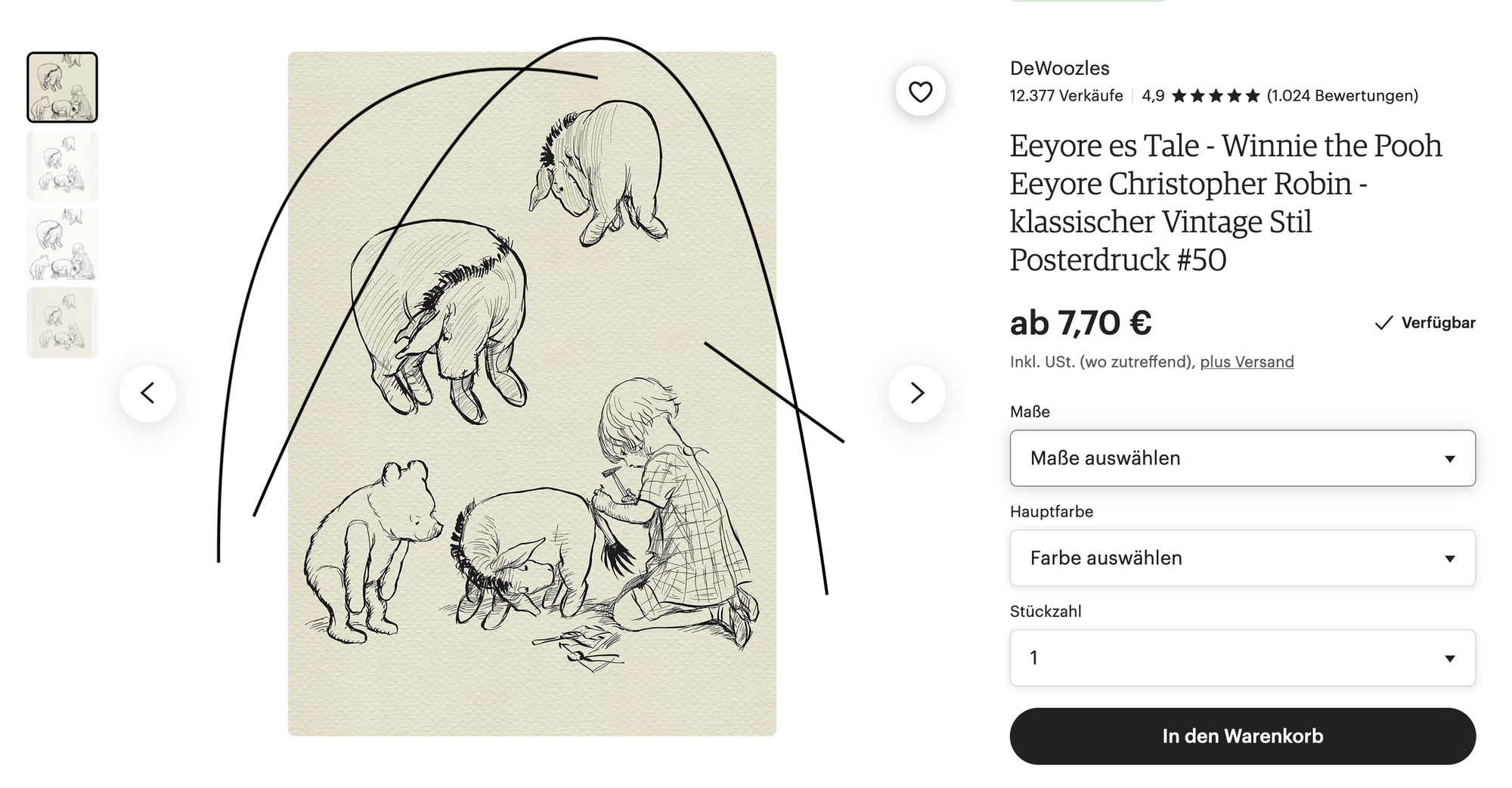

EN: Lukas Ludwig, Untitled (DeWoozles), 2021. Digital print, variable size.

DE: Lukas Ludwig, Untitled (DeWoozles), 2021. Digitaldruck, Maße variabel.

A black and white drawing of Winnie the Pooh and Christopher Robin pinning the tail on Eeyore the donkey. The image is a screen shot of a print the artist is purchasing for €7,70.

In her highly regarded study Black Sun: Depression and Melancholy (1987), psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva writes:

In ihrer vielbeachteten Studie Schwarze Sonne. Depression und Melancholie (1987) schreibt die Psychoanalytikerin Julia Kristeva:

I have assumed depressed persons to be atheistic—deprived of meaning, deprived of values. For them, to fear or to ignore the Beyond would be self-deprecating. Nevertheless, and although atheistic, those in despair are mystics—adhering to the preobject, not believing in Thou, but mute and steadfast devotees of their own inexpressible container. It is to this fringe of strangeness that they devote their tears and jouissance. In the tension of their affects, muscles, mucous membranes, and skin, they experience both their belonging to and distance from an archaic other that still eludes representation and naming, but of whose corporeal emissions, along with their automatism, they still bear the imprint. Unbelieving in language, the depressive persons are affectionate, wounded to be sure, but prisoners of affect. The affect is their thing.13

“Wir sind vom Depressiven als Atheisten ausgegangen – allen Sinns, allen Werts beraubt. Er entwürdigte sich, würde er das Jenseits fürchten oder auch nur ignorieren. Doch wie atheistisch er auch immer sein mag, der Verzweifelte ist vor allem Mystiker: Er klebt an seinem Prä-Objekt, ist kein Du-Gläubiger, sondern stummer und unerschütterlicher Anhänger seines eigenen unsagbaren Containers. Diesem Saum von Fremdheit widmet er seine Tränen und seine Lust. [...] Der Depressive glaubt nicht an die Sprache, er ist ein vom Affekt Gezeichneter, ein vom Affekt gewiß Verletzter, aber auch Gefesselter. Der Affekt, das ist sein Ding.”13

Eeyore’s depressive-melancholic enjoyment begins with the experience of the inadequacy of his own desire, just as much as of the inadequacy of the concept as a mediator between the self and the world. His mastery is of skepticism towards everything particular and manifest, the disavowal of the object in favor of a lack that has no worldly equivalent. The pre-object that Kristeva refers to here can also be described as a reaction to the foreignness of the world of signifiers, which appears to the ego solely as a boundary. The failure of the concept lies here in the necessity of opposition, of the separation between “me” and the thing, which only permits the experience of alienation. All that remains is suffering and sadness as an affective mood, resonating with the process of deterioration. The organism brings itself into an intoxicating resonance with a withdrawal—a withdrawal of energies from the delicate ramifications of its own rootedness in the world, for the benefit of another. Depression does not in the process simply erase subjective enjoyment of the object, but rather replaces it through a surrender to affect, to unfulfillable desire, to the mourning of a lost unity. This surrender of self to suffering is by no means a decision to die, but rather a reaction of the subject to a genuinely experienced loss. In terms of an ecology of enjoyment, suffering enables the continuation of a mood, and thereby of an emotional connection to the surrounding world.

Eeyores depressiv-melancholisches Genießen beginnt mit der Erfahrung der Unzulänglichkeit des eigenen Begehrens, ebensosehr der Unzulänglichkeit des Begriffs als Vermittler zwischen dem Selbst und der Welt. Seine Meisterschaft ist die Skepsis allem Einzelnen, Manifesten gegenüber, ist die Verleugnung des Objekts zugunsten eines Verlusts, der keine weltliche Entsprechung findet. Das Prä-Objekt, von dem Kristeva hier spricht, lässt sich insofern auch als eine Reaktion auf die Fremdheit der Welt der Signifikanten, die sich dem Ich einzig als Grenze eröffnet, beschreiben. Das Scheitern des Begriffs liegt hier in der Notwendigkeit der Opposition, der Trennung zwischen mir und dem Ding, die nur mehr die Erfahrung einer Entfremdung zulässt. Was bleibt, ist das Leiden und die Trauer als eine affektive Stimmung, eine Resonanz mit dem Verfall. Der Organismus bringt sich in eine rauschhafte Resonanz mit einem Rückzug, einem Rückzug von Energien aus den feinen Verästelungen, der eigenen Verwurzelung in der Welt zugunsten eines Anderen. Die Depression löscht das subjektive Genießen am Objekt dabei nicht einfach aus, sondern ersetzt es durch eine Überantwortung an den Affekt, an die unerfüllbare Sehnsucht, die Trauer um eine verlorene Einheit. Diese Überantwortung des Selbst an das Leiden ist gerade keine Entscheidung zum Tode, sondern eine Reaktion des Subjekts auf einen real empfundenen Verlust. Im Sinne einer Ökologie des Genießens ermöglicht das Leiden weiterhin eine Stimmung und darin einen emotionalen Bezug zur Umwelt.

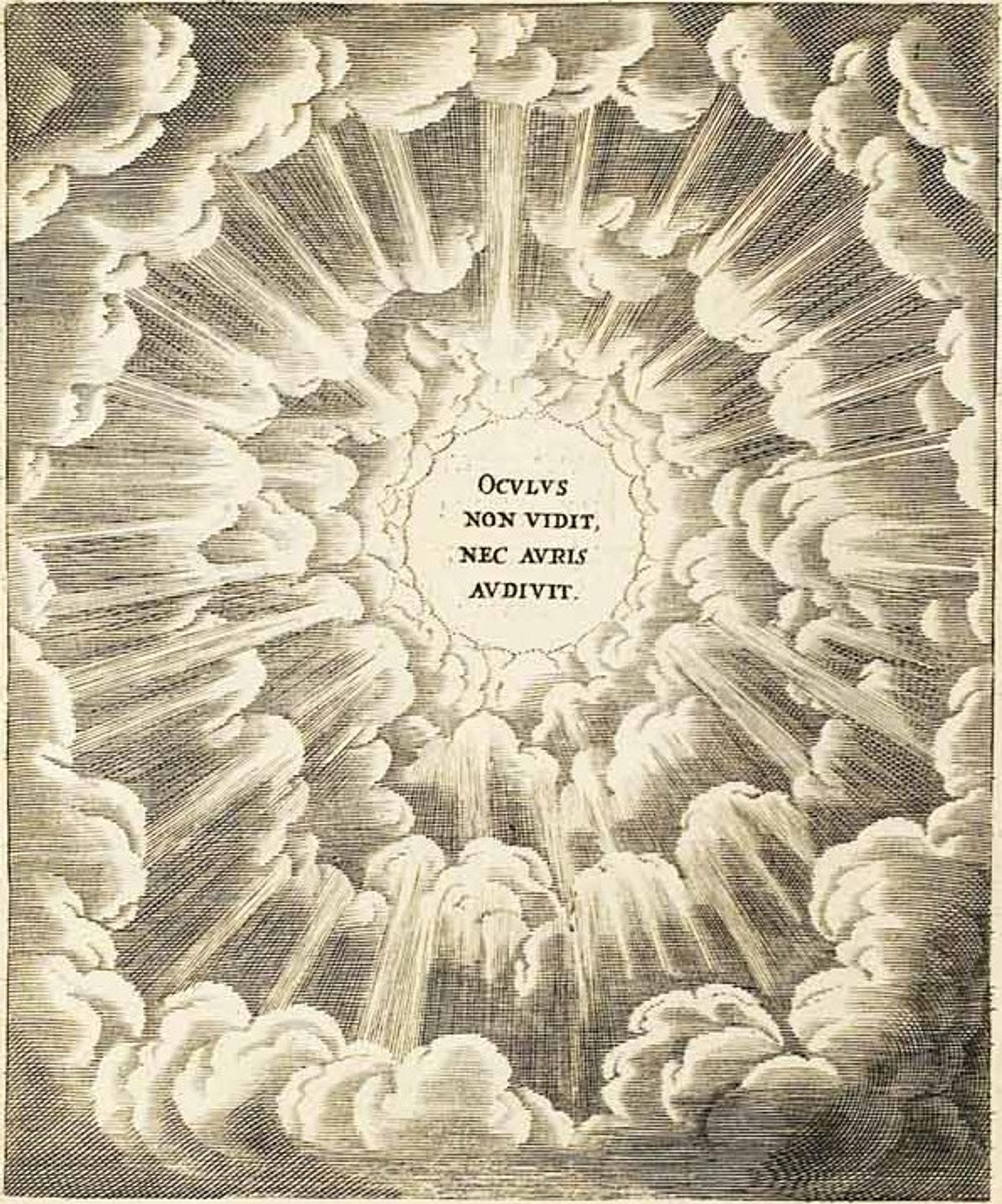

EN: OCVLVS NON VIDIT, NEC AVRIS AVDIVIT (“What no eye has seen, nor ear heard”, 1 Corinthians 2:9), appearing in: Otto van Veen, Amoris Divini Emblemata Studio Et Aere Othonis Vaenii Concinnata, Antwerp, 1660.

DE: OCVLVS NON VIDIT, NEC AVRIS AVDIVIT (Kein Auge hat gesehen und kein Ohr gehört, 1 Kor 2,9) erschienen in: Otto van Veen, Amoris Divini Emblemata Studio Et Aere Othonis Vaenii Concinnata, Antwerpen 1660.

A series of clouds surround a circle, which seems like the entryway to enlightenment. In the centre appears text in Latin, “What no eye has seen, nor ear heard”, from 1 Corinthians 2:9.

Following Kristeva, the donkey thus enters into proximity with the mystics, yet this mystical experience takes place precisely in the absence of the self. It is worth briefly noting here that mysticism finds a home in various religions: Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Taosim, Judaism—the list goes on. What unites these elements across religions is the search for the experience of divine or absolute reality. In the context of Christian mysticism, this led to the development of the concept of Unio Mystica (mystical union), which denotes the reunification or wedding of the human soul with God.14 In contrast to contemporary conceptions of experience and constructions of the subject, which in line with an economy of experience understand the productive self as a repository of experiences, the Unio Mystica can be described as a refuge of impersonal enjoyment, one which initially presents itself as a cloud of unknowing.15 The mystical experience is thereby tantamount to a temporary erasure of the self, in the sense of a surrender, an opening up to a non-human entity. What remains is a field of passive attention, of an affective reality set apart from the possibility of operative access. Affect skips ahead of thought, pre-empting it—the hide, in the case of the donkey, is quicker than the word. At this point it becomes clear why the mystical experience can never fully be explained, and in fact when seen in this light is not an experience at all, but rather something indivisible and incommunicable—who exactly is it that would be able to speak of it?

Kristevas Gedanken folgend, rückt der Esel damit in die Nähe der Mystiker*innen, findet doch gerade die mystische Erfahrung in Abwesenheit des Selbst statt. Hier sei kurz angemerkt, dass die Mystik keine ausschließlich christliche Tradition ist. Mystische Strömungen finden sich gleichermaßen im Islam, im Hinduismus, Buddhismus, Daoismus, Judaismus et cetera. Was diese Strömungen in gewisser Weise eint, ist die Suche nach der Erfahrung einer göttlichen oder absoluten Wirklichkeit. Im Kontext der christlichen Mystik wurde hier der Begriff der Unio Mystica geprägt, der die Wiedervereinigung oder Vermählung der menschlichen Seele mit Gott bezeichnet.14 Im Kontrast zu zeitgenössischen Erfahrungsbegriffen und Subjektkonstruktionen, die das produktive Selbst im Sinne der Erlebnisökonomie als Träger von Erfahrungen begreifen, lässt sich die Unio Mystica als ein Hort unpersönlichen Genießens beschreiben, der sich erst in einer Cloud of Unknowing, einer Wolke des Nichtwissens eröffnet.15 Dabei kommt die mystische Erfahrung einer temporären Auslöschung des Selbst im Sinne einer Überantwortung, eines Offen-Werdens für ein Nichtmenschliches gleich. Was bleibt, ist ein Feld passiver Aufmerksamkeit, einer affektiven Realität abseits der Möglichkeit operativen Zugriffs. Der Affekt überspringt den Gedanken, kommt ihm zuvor—die Haut ist schneller als das Wort. An dieser Stelle wird klar, warum die mystische Erfahrung keine vollständige Erklärung findet, ja so gesehen überhaupt keine Erfahrung ist, ist sie doch unteilbar, unvermittelbar—wer sollte von ihr erzählen?

Sound: The kitchener's lament from APPENDIX (2020) by Lukas Ludwig.

In contrast with the emphatic nature of the concept of mystical experience, today a highly contentious one, Denys Turner’s The Darkness of God: Negativity in Christian Mysticism (1998) points us toward the neo-Platonic origins of mystical theology. Beginning with the mystical writings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, which were composed at the beginning of the 6th century, Turner identifies an “awareness of the ‘deconstructive’ potential of human thought and language which so characterized classical medieval apophaticism” in early theological Christian discourses.16 In brief, apophatic or negative theology is based on the fundamental otherness of God, which places it beyond the realm of knowledge or experience. As a result, apophatic theology seeks to find God through the language of negation. One example of the radicality of this approach can be found in the work of Irish theologian, philosopher, poet, and later translator of Pseudo-Dionysius John Scotus Eriugena, born in 810. Scotus insists that God is nothing, because divinity does not occupy a state of being or existence in a way that is familiar to us.17 This non-knowledge of the divine being is transformed into a positive knowledge of the implied boundaries of identifying, attributing language. Making reference to the Greek etymology of the term 'theology', Turner consequently provides an additional definition of apophatic theology as “that speech about God which is the failure of speech.”18 Interestingly, this rather paradoxical insight (knowledge of an impossibility) need not necessarily lead to monastic silence but instead an opening up of language to embrace the poetic, literary imagery, metaphor, rhythm, displacement and repetition; an excess of expression on the one hand, and the unheard-of silence of the text on the other.

Gegenüber der Emphase des Begriffs der mystischen Erfahrung, einem heute durchaus umstrittenen Begriff, macht uns Denys Turner in The Darkness of God: Negativity in Christian Mysticism (1998) auf die neo-platonischen Ursprünge der mystischen Theologie aufmerksam. Ausgehend von den mystischen Schriften des Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita, die Anfang des 6. Jahrhunderts nach Christus verfasst wurden, identifiziert Turner in den frühen christlich-theologischen Diskursen ein: “[…] Bewusstsein für das ‘dekonstruktive’ Potenzial menschlichen Denkens und der Sprache, das den klassischen mittelalterlichen Apophatismus auszeichnet.”16 Kurz zusammengefasst geht die apophatische oder negative Theologie von der fundamentalen Andersartigkeit Gottes aus, aus der die Unvermittelbarkeit des göttlichen Wesens folgt. Dementsprechend sucht die apophatische Theologie Gott in der sprachlichen Negation. Ein Beispiel für die Radikalität dieser Verneinung findet sich im Werk des irischen Theologen, Philosophen, Dichter und späteren Übersetzers der Schriften des Pseudo-Dionysius John Scotus Eriugena, der 810 nach Christus geboren wurde. Scotus insistiert, dass Gott nichts (nothing) ist, da er in keiner uns verständlichen Art und Weise ein Sein oder eine Existenz besitzt.17 Dieses Nicht-Wissen um das Wesen Gottes wird dabei ebenso zu einem positiven Wissen um die impliziten Grenzen identifizierender, attribuierender Sprache. In Rückbezug auf die griechische Etymologie des Begriffs Theologie definiert Turner die apophatische Theologie folglich auch als “[…] diejenige Rede über Gott, die das Versagen der Sprache ist.”18 Auf diese durchaus paradoxe Erkenntnis (das Wissen einer Unmöglichkeit) folgt interessanterweise gerade nicht zwangsläufig das mönchische Schweigen, sondern eine Öffnung der Sprache für das Poetische, für das literarische Bild, die Metapher, den Rhythmus, die Verschiebung und Wiederholung, für das Zu-viel-sagen auf der einen und das unerhörte Schweigen des Textes auf der anderen Seite.

Here we encounter a kind of change in the sign: negation or critique is inverted and becomes an affirmation of an inadequacy that conversely enables writing and speaking as a secular practice. We have this change to thank for the metaphorical opulence of mystical writings, whose vocabulary is drawn from a variety of secular discourses, including those concerning science, literature, art, sex, politics, law, war, and physiology, among others. In the end, a combining or reconciling with the nonverbal also appears possible within language itself.

Hier begegnet uns eine Art Vorzeichenwechsel: die Negation beziehungsweise Kritik kippt und wird zur Affirmation einer Unzulänglichkeit, die wiederum ein Schreiben und Sprechen als weltliche Praxis ermöglicht. Diesem Wechsel verdanken wir die metaphorische Opulenz der mystischen Schriften, deren Vokabular sich aus einer Vielzahl weltlicher Diskurse, sei es Wissenschaft, Literatur, Kunst, Sex, Politik, Recht, Krieg, Physiologie et cetera speist. Die Vermählung oder Versöhnung mit dem Nichtsprachlichen scheint auch in der Sprache selbst möglich.

On the basis of this shift, the mystical self-delivery of the donkey to its object, to its refuge of impersonal desire, is also never fully accomplished—the completion of the process of self-abnegation can ultimately only be achieved through death. In this context, Kristeva focuses particular attention on the language of the depressed, which despite being slowed down and disrupted by silences also contains phonetic modulations, breaks in speech, and sudden jumps; along with an exceptional cognitive lucidity, these are also accompanied by a highly singular and creative capacity for association.19 And although the depressed are less and less able to avoid enjoying the deterioration of the world to the benefit of an ineffable other, in their mode of speaking the possibility of communication announces itself. Seen in light of this subjective constellation, depression appears not only as a pathology to be treated but also as a discourse, or rather a language, which in the face of a “real” or “absolute” that resists interpretation retreats to the borderlands of linguistic expression. Kristeva’s study, which she based on both literary analysis as well as case studies from her own psychoanalytic practice, provides us with another perspective on depression, showing it to be a source of creativity as well as suffering. To some extent, she also opens up another, more distantiated view on a world that no longer provides a home for the depressed. It is important to note that this is not an attempt to make the depressed subject the trustee of a kind of preconceptual or even “primordial” creativity, per se, and thus convert depression into a productive force. We are precisely as far away as possible from contemporary paradigms of creativity which insist on unbounded productivity and the creative self-realization of the individual and thereby render political organization and subjective reinscription within a historical context or a society impossible.

Diesem Übergang folgend ist auch die mystische Selbst-Auslieferung des Esels an sein Ding, an den Hort unpersönlichen Genießens, im Hier und Jetzt nie vollständig—die Vervollständigung der Selbst-Verleugnung verspricht der Tod allein. Julia Kristeva widmet sich in diesem Kontext vor allem dem Sprechen der Depressiven, in dem sich trotz der verlangsamten und von Stille unterbrochenen Sprache lautliche Modulationen, Abbrüche und Sprünge ausmachen lassen, die mitunter mit einer außergewöhnlichen kognitiven Luzidität, einer höchst singulären und kreativen Assoziationsfähigkeit einhergehen.19 Und wenngleich die Depressiven sich dem Genuss des Verfalls der Welt zugunsten eines unaussprechlichen Anderen immer weniger entziehen können, eröffnet sich in ihrem Sprechen die Möglichkeit der Mitteilung. Die Depression erscheint im Sinne dieser Subjektkonstellation nicht nur als zu behandelnde Pathologie, sondern als ein Diskurs, also wiederum eine Sprache, die sich angesichts eines sich der Sinngebung entziehenden Realen oder Absoluten in die Randbereiche sprachlichen Ausdrucks zurückzieht. Kristevas Studie, die sich sowohl auf die Analyse literarischer Texte als auch auf Fallbeispiele ihrer eigenen analytischen Praxis stützt, eröffnet uns hier einen anderen Blick auf die Depression als Quelle von Leiden, aber auch von Kreativität. Sie eröffnet gewissermaßen einen anderen, entfernten Blick auf eine Welt, die den Depressiven nicht länger beheimatet. Dabei geht es nicht darum, dem depressiven Subjekt per se die Trägerschaft einer Art vorbegrifflichen oder gar “ursprünglichen” Kreativität zu unterstellen und in diesem Sinne zu einer Produktivkraft umzubauen. Wir sind gerade am weitesten entfernt von zeitgenössischen Kreativitätsparadigmen, die auf uneingeschränkte Produktivität und kreative Selbstverwirklichung des Individuums insistieren und damit die Möglichkeit politischer Organisation und die subjektive Wiedereinschreibung in einen historischen Kontext oder eine Gesellschaft unmöglich machen.

Sound: Lord of Merci! from APPENDIX (2020) by Lukas Ludwig.

Back to our long-eared companion: earlier on, we had positioned the donkey at a site of transition, a point of exchange, of conceptual instability and shifting physical and psychic forces. We can now formulate this configuration more precisely as a mode of survival in the presence of a “real” that is to some extent ineffable, something that resists, that is unconceptualizable, inhuman, and absolute. Both ways of relating to this “real”—that is, the binding of the object mediated through the difference of signifiers, on the one hand, and the surrendering of the self to affect on the other—both facilitate, in very different ways, a kind of feedback, a connection to the world. Both sides of this configuration thus appear not only as boundaries but also as thresholds of creative power. Put another way, we can say that the deterioration of language also takes place within language itself, and although the enjoyment of this deterioration is addictive, this negative pleasure finds forms of expression that can appropriately be located within the realm of the aesthetic: forms which in turn facilitate a discourse which itself enables an inscribing of the self into the world. It can perhaps be said that the donkey is always standing where enjoyment battles with signifiers, where the body absconds, where critique betrays its object and reveals itself as belief. The donkey invites us in, tricks us into staying awhile at this site of transition, into lingering at the point of contradiction—indeed, what would we be without it?

Zurück zum Langohr: Wir hatten den Esel vorhin an einem Übergang, an einer Stelle des Austauschs, der Instabilität des Begriffs und des Wechsels physischer und psychischer Kräfte positioniert. Wir können diese Konstellation nun genauer fassen, nämlich als ein Überleben im Angesicht eines gewissermaßen unaussprechlichen Realen, eines Widerständigen, Unbegrifflichen, Unmenschlichen, Absoluten. Beide Formen der Bezugnahme auf dieses Reale, also die Objektbindung vermittelt durch die Differenz der Signifikanten auf der einen Seite und die Überantwortung des Selbst an den Affekt auf der anderen Seite, ermöglichen auf sehr unterschiedliche Art und Weise eine Art Feedback, einen Bezug zur Welt. Beide Seiten dieser Konstellation erscheinen dabei nicht nur als Grenzen, sondern ebenso als Schwellen schöpferischer Kraft. Umgekehrt formuliert findet auch der Verfall der Sprache innerhalb der Sprache statt, und obwohl der Genuss dieses Verfalls süchtig macht, findet dieses negative Genießen Formen des Ausdrucks, die sich zurecht im Bereich des Ästhetischen verorten lassen: Formen, die wiederum einen Diskurs und darüber eine Einschreibung des Selbst in die Welt ermöglichen. Vielleicht lässt sich sagen, dass der Esel immer dort steht, wo das Genießen mit dem Signifikanten kämpft, wo sich der Körper davonstiehlt, wo die Kritik ihr Objekt verrät und sich als ein Glauben eröffnet. Der Esel lädt uns ein, er verführt uns für eine Weile am Ort des Übergangs zu verharren, im Widerspruch zu verweilen—was wären wir nur ohne ihn?

At this point it is hardly surprising that when it comes time for Christopher Robin to bid his animal friends farewell, Eeyore recites a poem. The literary and depressed donkey offers up a perfect example of a different way of speaking that exists at the outer limit of language, one which enables a restitution of the self aligned to a new cartography, a community, an audience. Figuratively speaking, what we see here is a closing of the circle between muzzle and tail, the outline of the donkey now appearing. Donkey circulates around this bypass.

Es ist an dieser Stelle nicht allzu verwunderlich, dass Eeyore zum Abschied von Christopher Robin ein Gedicht rezitiert. Der literarisch-depressive Esel bietet uns hier exemplarisch ein anderes Sprechen am Rand der Sprache, die eine Restitution des Selbsts im Rhythmus einer neuen Kartografie, einer Gemeinschaft, einer Zuhörerschaft ermöglicht. Bildlich gesprochen schließt sich hier der Kreis zwischen Schnauze und Schwanz, die Silhouette des Esels erscheint. Donkey zirkuliert um diesen Kurzschluss.

EN: Lukas Ludwig. Untitled (donkey legs / front hoofs), 2021. Digital print, variable size.

DE: Lukas Ludwig. Untitled (donkey legs / front hoofs), 2021. Digitaldruck, Maße variabel.

Elongated legs of a donkey take up most of the image. The hooves are standing firm, but shy, and the brown furry legs seemed determined, demonstrating its stubborn character. A black bar appears at the bottom of the image.

APPENDIX

Eeyore’s Poem

Christopher Robin is going

At least I think he is

Where?

Nobody knows

But he is going—

I mean he goes

(To rhyme with ‘knows’)

Do we care?

(To rhyme with ‘where’)

We do

Very much

(I haven't got a rhyme for that ‘is’ in the second line yet. Bother.)

(Now I haven't got a rhyme for bother. Bother.)

Those two bothers will have to rhyme with each other

Buther

The fact is this is more difficult

than I thought,

I ought—

(Very good indeed)

I ought

to begin again,

But it is easier

To stop

Christopher Robin, good-bye

I

(Good)

I

And all your friends

Sends—

I mean all your friend

Send—

(Very awkward this, it keeps

going wrong)

Well, anyhow, we send

Our love

END. 20

Sound: Clerestory by James Rushford. Live recording at Hospitalkirche Stuttgart, 2017. Courtesy Lukas Ludwig. Copyright James Rushford.

Endnotes

See Jutta Person, Esel: Ein Portrait (Donkey: A Portrait) (Berlin: 2013).

See Martin Vogel, Onos Lyras: Der Esel mit der Leier (Onos Lyras, or: The Donkey with the Lyre) (Düsseldorf: 1973).

See Veb, CRAZY DONKEY SOUND! | Top 5 Donkey Sounds, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7EC4nQ6Qqk, last accessed 09.02.2022.

Otto Keller, Die antike Tierwelt (The Animals of the Ancients), Vol. 1 (Leipzig: 1909), 260.

Apuleius, The Golden Ass, trans. E.J. Kenney (London: 1998), p. 14.

See Jutta Person, Esel: Ein Portrait (Donkey: A Portrait) (Berlin: 2013).

Ibid., 10.

See Wolfgang Lempfrid, radio manuscript for “Feasts of the Ass and of Fools: Medieval Music between the Church and Heresy”, Süddeutsche Rundfunk, 1993, http://www.koelnklavier.de/texte/altemusik/eselsfeste.html, last accessed on 09.02.2022.

See Christopher Milne, The Enchanted Places: A Childhood Memoir (Boston: 1974).

See Alan Alexander Milne, Once on a Time (London: 1917).

Rick Reinert (Prod.), Winnie-the-Pooh and a Day for Eeyore, Walt Disney Productions, 1983.

A “leap of faith” as formulated by Søren Kierkegaard insists upon a fundamental separation between human existence (and rationality/reason) and the eternal, the absolute, or the divine. Although this difference is mediated (to put it briefly) by the Christian topos of God taking human form in Christ, it presents human beings with an unresolvable paradox. When Kierkegaard writes that “faith begins precisely where thinking leaves off”, the leap of faith is intended to be seen as a liberation from ethical and epistemic conceptions of belief in service of the radical gamble that belief constitutes, a necessarily irrational action that requires ongoing repetition. See Søren Kierkegaard, Philosophical Fragments, 1844.

Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholy, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: 1987), 14.

Uta Störmer-Caysa, Einführung in die mittelalterliche Mystik (Introduction to Medieval Mysticism) (Leipzig: 1998), 9.

See Denys Turner, The Darkness of God: Negativity in Christian Mysticism (Cambridge: 1998).

Ibid., 8.

See Karen Armstrong. The Case for God (New York: 2009), 105

Turner, The Darkness of God: Negativity in Christian Mysticism, 20.

See Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholy, 59.

A.A. Milne, The House at Pooh Corner (New York: 1928), 106.

Endnoten

Vgl. Jutta Person, Esel. Ein Portrait, Berlin 2013.

Vgl. Martin Vogel, Onos Lyras: Der Esel mit der Leier, Düsseldorf 1973.

Vgl. Veb, CRAZY DONKEY SOUND! | Top 5 Donkey Sounds, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7EC4nQ6Qqk, zuletzt abgerufen am 08.05.2021.

Otto Keller, Die antike Tierwelt, 1 Bd., Leipzig 1909, S. 260.

Apuleius, Der goldene Esel, Fischer E-Books 2011, https://www.fischerverlage.de/buch/apuleius-der-goldene-esel-9783104012025, zuletzt abgerufen am 08.05.2021.

Vgl. Jutta Person, Esel. Ein Portrait, Berlin 2013.

Ebd.: S. 10.

Vgl. Wolfgang Lempfrid, Sendemanuskript Von Narren- und Eselsfesten. Mittelalterliche Musik zwischen Kirche und Ketzerei, 1993, http://www.koelnklavier.de/texte/altemusik/eselsfeste.html, zuletzt abgerufen am 08.05.2021.

Vgl. Christopher Milne, The Enchanted Places: A Childhood Memoir, Boston 1974.

Vgl. A.A. Milne, Once on a Time, London 1917.

Rick Reinert (Prod.), Winnie-the-Pooh and a Day for Eeyore, Walt Disney Productions 1983.

Der Sprung in den Glauben ist ein von Søren Kierkegaard geprägter Begriff, der auf eine fundamentale Differenz zwischen dem Ewigen, Absoluten oder Göttlichen und der menschlichen Existenz, gleichermaßen der Rationalität bzw. Vernunft insistiert. Wenngleich diese Differenz im Topos der christlichen Menschwerdung Gottes verkürzt gesagt vermittelt ist, stellt sie für den Menschen ein unauflösbares Paradoxon dar. Wenn Kierkegaard schreibt: „Der Glaube beginnt gerade da, wo das Denken aufhört“, ist der Sprung in den Glauben vor allem ein Befreiungsschlag gegenüber ethischen bzw. erkenntnisbezogenen Glaubensbegriffen zugunsten der radikalen Wagnis des Glaubens, ein notwendigerweise irrationaler Schritt, der der permanenten Wiederholung bedarf. Vgl. Søren Kierkegaard, Philosophische Brocken, 1844.

Julia Kristeva, Schwarze Sonne. Depression und Melancholie, Frankfurt 2007, S. 22 f.

Uta Störmer-Caysa, Einführung in die mittelalterliche Mystik, Leipzig 1998, S. 9.

Vgl. Denys Turner, The Darkness of God: Negativity in Christian Mysticism, Cambridge 1998.

Ebd.: S. 8.

Vgl. Karen Armstrong. The Case for God, New York 2009, S. 105.

Denys Turner, The Darkness of God: Negativity in Christian Mysticism, Cambridge 1998, S. 20.

Vgl. Julia Kristeva, Schwarze Sonne. Depression und Melancholie, Frankfurt 2007, S. 67.

A.A. Milne, The House at Pooh Corner, New York 1928, S. 106.

Acknowledgements

Donkey has been extended into an hour-long audio book, complemented with music by Lukas Ludwig and composer and musician James Rushford, who generously gave the donkey a voice.